Field Report - Autumn 2024

Balmy above-zero temperatures are great for studying active hydrology, but sometimes liquid water can get in the way. Some of our geophysical techniques work much better when the ice is fully frozen. For that reason, our second field block of 2024 was planned later in the year, in the early autumn, to target colder conditions. This meant there was actual darkness during the night (a novelty for many polar scientists!), and made day-to-day activities like finding drinking water and going to the toilet a little more… exciting.

Quick stats

26km of radar data

3 active seismic lines

113 passive seismic nodes retrieved

~16kg chocolate consumed

Goals

Our main goal during this field block was to collect geophysical data, in order to reveal the location of the glacier bed (i.e. the thickness of the ice) and internal structures within the ice, as well as any information we could glean about the properties of the bed. Is there water down there, or solid rock, or perhaps a mix of the two?

We also serviced the existing instruments and downloaded the data they had collected since we were last on the glacier. This is important, as it’s always possible for them to break or even disappear once we leave them over the winter!

Geophysical Methods

The vast majority of geophysical methods come down to a simple principle: send a wave into the ground, let it reflect off whatever is down there, and then measure the reflection when it comes back up. Waves reflect off interfaces where there is a change in material properties; a clear example of this is the interface between ice and rock (or water) at the base of the glacier.

These methods are listed approximately in order of success… Spoiler, not all were successful!

Active seismics: stop, hammer time!

Seismic methods are the most hands-on form of the send-a-wave-down-and-measure-the-reflection principle. We used a hammer and plate method, which consists of literally hitting a plastic plate with a sledgehammer to create a vibrational wave, which reflects off subsurface interfaces and comes back up to be measured on instruments called ‘geophones’ at the surface. We deployed geophones every 2m over over stretches of 200m, and the difference in time between the vibrational waves arriving at one geophone relative to the next can give us a lot of information about the location and geometry of subsurface interfaces such as the glacier bed.

We spent $ days running seismic surveys in 3 different locations, deliberately targeting the centre, margin and outside of ‘Lake’ 1 so that we can compare the data collected between those locations and determine if there are any significant differences in bed properties.

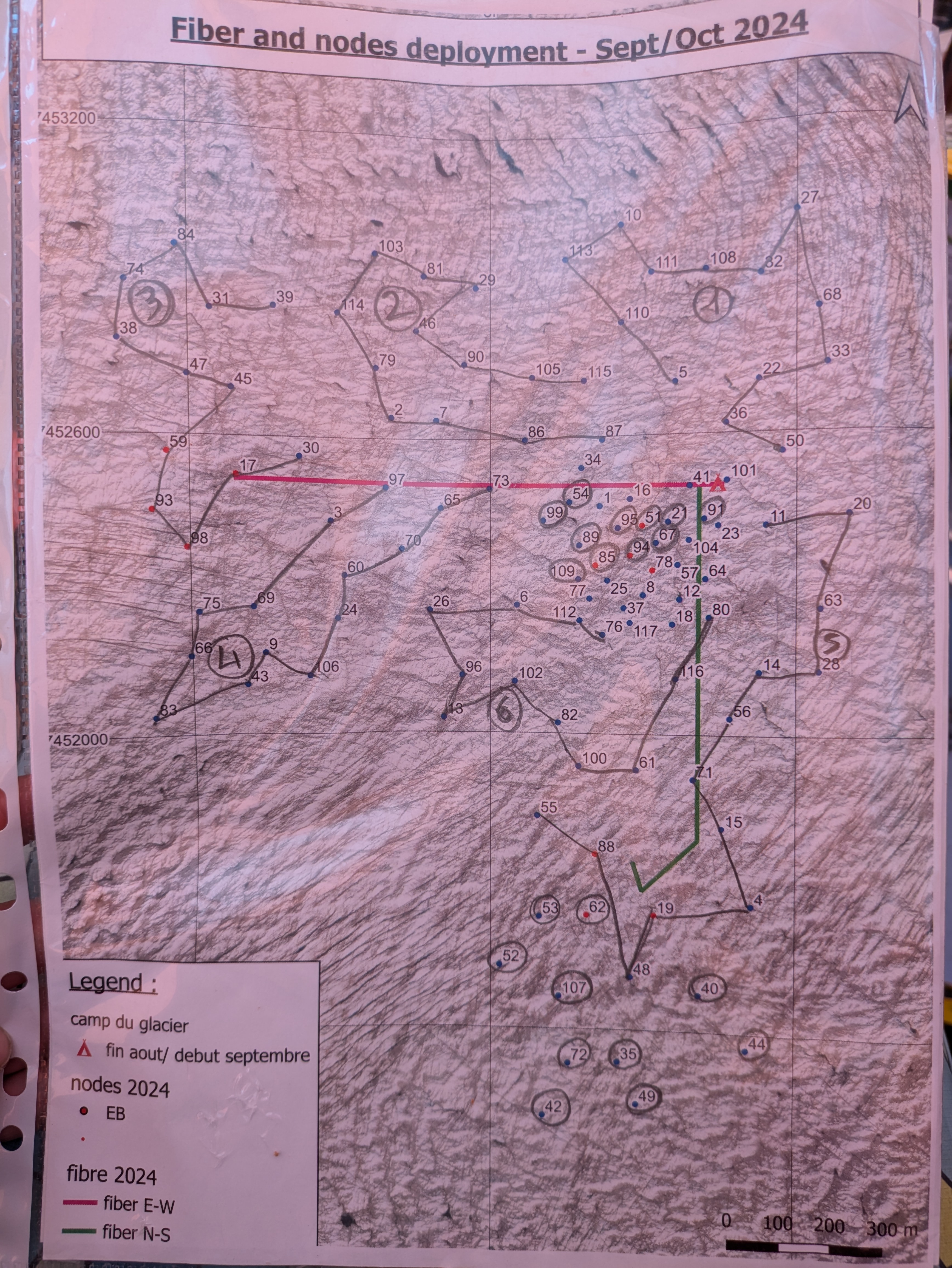

Passive seismics: node to self

During the June-July field block this year, seismic recievers (“nodes”) were deployed in a network across the glacier. These receivers sit and pick up vibrations in the ice as they happen, to collect similar data to our active seismic survey, but ‘passively’ while we aren’t there. We spent two days collecting all 113 of these nodes so that the data could be downloaded. This was no easy task, as the nodes had frozen into the ground and needed to be chipped out one by one. Luckily we had some keen rogainers in our midst, and this quickly turned into a race. Of course it’s not important who won, it was all about participation and absolutely nobody is sore about losing.

Radar: glacio killed the radio star

Ice-penetrating radar is a method of sending radio waves into the ice, and detecting the returns using an antenna on the surface. The system we used is mounted on two sleds (the transmitter on one, and receiver on the other) with the antenna between. These can be dragged along the ice while continuously transmitting, allowing data to be collected over a large area. Sounds easy, right??

However, Isunnguata Sermia is not so easy to pin down. The uneven topography made dragging the sleds in a straight line and at a consistent speed extremely difficult, and it took a team of four people (one navigator, one chief dragger and a minder for each sled) to collect radar lines. Against the odds, we managed to collect 26 km of data over ‘lakes’ 1 and 2, with the glacier bed clearly visible!

Unfortunately this chapter of the story ends in a tragic denouement, as the receiver sled took a swift dive into a crevasse and could not be revived (despite the efforts of some very capable trauma surgeons). However, we still managed to collect a huge amount of data, and consider this overall a big success.

TEM: a.k.a the Tedious Esoteric Method

The correct name for this method is Transient Electromagnetics, however we have suggested a more accurate name in this subheading. To collect TEM data, we laid out cables in a 100m square on the galcier surface around a receiver. When a transmitter is switched on, a current runs through the cables and creates an electromagnetic field, which is then switched off. This causes a response magnetic field to form and then decay away within the ice, and this response field is measured by the receiver. Theoretically, this should give us information about the electrical resistivity of the subsurface (useful to us because rock is more resistant than ice, which is in turn more resistive than water). As perceptive readers might have gleaned already, we did not have success with this method. The terrain on Isunnguata Sermia makes it extremely difficult to lay out the cables, and the presence of liquid water and crevassing meant that the transmitter was not powerful enough to return a meaningful signal. There were some suggestions of the TEM equipment taking an accidental trip down a crevasse, but in the end it was spared and made it back to Kangerlussuaq unharmed but ashamed.

Instrument servicing

We took the opportunity to service several existing instruments. This involved trekking out to the installations all accross the glacier, checking that they were still functioning, and recording the data. As the glacier surface is constantly ablating away, new poles needed to be installed and solar panels lowered before they could topple over.

These instruments measure GPS location to cm-scale accuracy, alongside some seismic receivers to pick up vibrations in the glacier, and weather stations to record the conditions throughout the year.